This is another catch-up post for a number of day trips that we've taken in the past three weeks. Since returning from Barcelona, we've been able to settle our visa situation until the spring, California suffered a number of wildfires, Halloween happened (yes, it's kind of a thing here in Portugal), there were world-wide anti-government protests (Algeria, Bolivia, Chile, Catalonia, Hong Kong, Iraq, Lebanon), and the US House committees have completed their "quid pro quo" investigations of the Trump Administrations, and will begin public hearings next week. And in that time, we also went to ...

MAAT

November 3 – The Museu de Arte, Arquitetura e Tecnologia (MAAT) is in the Lisbon bairro of Belém. It's quite a long way from the historic center, but we are in the mood for a good walk. Despite some moments of misty spray, we find the walk along the Rio Teju is a great way to "view" Lisbon. Usually, you get Lisbon views from a miradouro, a high viewpoint, where you walk up winding stairs and alleys to the top of a hill, and you reach the top and the city hits you. Walking along the river, you get constant visual contact with Cristo Rei, the Ponte Vinte e Cinco de Abril, but then also the constant changing cityscape along the hills.

MAAT is two buildings: a swoopy-low, Calatrava-like "dune-cavern", and an enormous, decommissioned power plant. The contemporary building, from 2016, is by Amanda Levete Architects. It's a "dune" is because the roof garden, which provides a slightly elevated view of the river side. It's also a cavern which contains a series of smaller, connected galleries on the lower level, and a larger, double-height space with a viewing ramp.

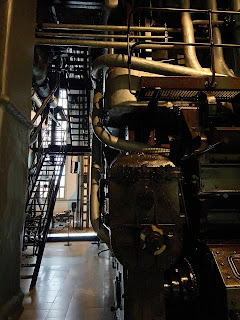

The old power plant originally opened in 1909, and the current building dates from 1930's, and includes an expansion from the 1950's. The plant was decommissioned in the 1970's, and served as the Museu da Electricidade in the 1990's. Inside, the power plant actually makes amazing gallery space, and the Trienal de Lisboa (Lisbon Architecture Triennale) is on display. Though a little esoteric even for an architecture nerd like me, the show was full of wonderful drawings and models – when there's a lot of architectural work is in a show, all I can do is marvel at the amount of time I know it takes to put it all together.

The Museu da Electricidade is still there, too, and the old industrial spaces have been put to astonishingly good use in telling the story of the plant. With lighting, sound, and a few well-placed mannequins, posed mid-shift, loading coal, or pushing ash carts, the power of the building lives on.

Miradouro da Senhora do Monte

November 5 – It's a beautiful autumn day in Lisbon, and we take a walk from our apartment to the Miradouro da Senhora do Monte in the bairro of Graça. One of the highest points in the city, what might elevate this miradouro above the miradouro at Castelo de São Jorge, is the fact that you are not standing *on* the Castelo, the Castelo is *in* the view. It may be the "biggest"or "widest" view of Lisbon, and the bairro of Graça is a great places to explore.

Évora

November 8 – We take a day trip to the ancient city of Ebora, now Évora. The trip is built around a tour given by Mário Carvalho of Ebora Megalithica to see a few of the pre-historical (archeological) sites dotting this compelling landscape, in the province of Alentejo. It's a ninety minute bus ride from Sete Rios, to travel back in time several thousand years.

Our first stop is to the Cromeleque dos Almendres, which dates from about 6,000 BCE. After watching several YouTubes previewing the site, I am shocked to find it barren and deeply eroded. The site itself is broad, and sloped to the east; its axis of symmetry is aligned to the sunrise on the equinoxes. We arrive at the site at about 10:30 in the morning, so the shadows cast in the pictures are to the northwest. The site is ringed with several dozen standing stones, of varying height, but all of a human scale, and all generally rounded. A few stones have curious markings which are hard to read in the sunshine: rings, crescents (moons), and hooks (shepherd staffs). They are roughly arranged to create an enclosed space – not like a "room" but more like a camp site. In the sharp sunlight, in the middle of an extensive grove of cork oaks, the standing stones create a striking contrast, in the clearing, against the craggy limbs.

Next stop is the Menhir dos Almendres, a solitary, four meter standing stone about 1400 meters to the southeast of the Cromeleque, which marks the rise of the sun at the summer solstice from the enclosure. Another menhir marks the winter solstice, about the same distance from the Cromeleque, but to the northeast. Mário tells us that the height and the orientation of the stones, which were all re-erected, are known by studying the "sockets" which are preserved in the geology; it is known that this stone was stood in the incorrect orientation, as the hook marking (barely visible in the flattened surface) should be facing east, toward the morning sun.

The third stop is to the Anta Grande do Zambujeiro. This is a tomb, where several skeletons were found buried in a ceremonial fashion, and dates from about 3,500 BCE. These very large stones are arranged in a typical layout for dolmen (burial structures) in the area, with a wide, flat stone at the back, and three narrower stones on each side, and the east-face entry passage, thus forming a kind of flattened octagon in plan. A wide cap stone lays behind the structure; it was broken when the earthen mound was removed from the stone structure. A rough metal structure stands cover, but is clearly nearing its end of life, and the design actually concentrates the rain within the excavated valley of the mound. We are told that it is unsafe to enter.

Such a shame these sites are not under the proper care of some local authority. Mário's excellent expositions are tinged with the regret that these sites are in serious threat, with no plan to preserve or protect them.

The afternoon is spent exploring the old city. From megaliths to Roman ruins, we find the Templo Romano de Évora in the center of town; we are told that its "nickname", the Templo de Diana, is not quite proper. Just a few columns remain standing of this hexastilo temple; if a typical double-square, it would have eleven columns a side. It's generous of the city to leave the area of the ruined temple "empty" where one may imagine the rest of the structure complete.

The Corinthian capitals are amazingly clean and white; the columns are deeply fluted and really grab the mid-day light. Wonderful to think that it's still here after two thousand years.

Next to the Templo is the Sé, the Cathedral of Évora and dates from about 1200-1300. We start at the top; not a crazy dramatic climb like some other churches. The tops of the entry towers are capped by cones covered colorful roof tiles and bright ochre moss. The cap of the crossing is an imposing, octagonal stone turret.

Inside, the Cathedral is remarkably plain, with even-cut, grey stones and clean, contrasting mortar lines. Oddly, there is a kind of altar, bright gold, crowded to the left side of the main nave, with a striking figure of the pregnant virgin. Above this, and to the rear, is a remarkable pipe organ, with vertical and horizontal horns. The chapels have some nicely ornamented pieces, but the most impressive space is the main choir itself, a highly ornamented, classical baroque ending to a plain gothic story. To each side of the choir, in each transept are false-perspective, barrel-vaulted chapels.

The cloisters are also available to the public. Like the main structure, these are heavy, gothic vaulted halls framing some nice views back to the church.

Our last stop in Évora is the Cappella dos Ossos, inside the Igreja de São Francisco. We so enjoyed our macabre visit to the crypt at the Igreja de São Francisco in Porto, we think this a must-see. The Cappella is a large, vaulted room completely plastered with human bones. I especially appreciate the bones used to delineate the pilasters and embedded arches, and the skulls used to trim the vaults.

No comments:

Post a Comment