Having finished our tours of Santo Spirito and the Stanza Segreta, we turn our attention to the museums of Firenze (Florence, pop 367,150 in 2022). During our last trip we visited the Uffizi and Accademia; next on the list is the Museo Nazionale del Bargello (Palazzo del Podestà, 13th century).

The Palazzo is a former courthouse, police office, and prison, but inside, it feels like a medieval nobleman's residence. Around the cortile, the coats of arms of the podestà (local magistrate) mark this as a civic building; they seem to feature a variety of animals and people with looping necks set atop armored helmets.

Near the entrance, in the north gallery, the sculptures are lined up as if they are spares. In the corner, a substantial queue of 'live' figures waits for a special exhibition. The Salone di Donatello is closed, but highlights from that room are in a temporary show.

The west gallery is cut by an enormous staircase; the gated archway at the landing may be from prison days. Around the other corners, heroic pieces inhabit the ground level, including Oceano (Giambologna, 1572-76) and Il Pescatorello ('fisher boy', Vincenzo Gemito, 1876).

After a lap of the cortile, with the queue shortened, we turn around and enter the special exhibit of Donatello. We are greeted on our left by Cupid ('Amore Attis', Donatello, 1440-43), and on our right by David (Andrea del Verrocchio, 1473-75 – Verrocchio's, we recall, is the studio that trained Leonardo). In the center of the small room is the famous David ('Bronze David', Donatello, c1440).

Even accounting for the temporary setting, the sculptures come across as 'creepy', especially the Cupid with his grotesque expression. Verrocchio's David looks even younger than Donatello's (historically controversial), and though his lower half is covered, the 'decorations' on his chest are 'unexpected'. And the shadowed face of Donatello's is strangely reminiscent of Michael Jackson. it's not the best cultural reference – which is to take nothing away from the obvious technique and skill in all these pieces.

A pair of lovely terracotta reliefs by Luca della Robbia, Madonna col Bambino ('Madonna della Mela',1441-45; 'Madonna del Roseto', 1460-70), helps break the tension, with the caption:

Ave Maris stella Dei mater alma[Hail Mary, star of God, soul of Mother]

On the back wall are two quatrefoil reliefs from Il Concorso per la Porta Nord del Battistero di Firenze ('competition for the Baptistry door'): Il sacrificio di Isacco (Lorenzo Ghiberti, 1401-02) and Il sacrificio di Isacco (Filippo Brunelleschi, 1401-02). Fantastic to see these two together, as they mark turning points in the careers of the artists and an important inflection point between Medieval and Renaissance art. The competition is a tie, but Brunelleschi refuses to work with Ghiberti. Ghiberti completes the Porta Nord, then goes on to design the Porta del Paradiso.

Meanwhile, Brunelleschi abandons sculpture and retreats to Rome where he draws and studies ancient buildings; he employs these techniques to build the Cupola del Duomo and invents a new system of linear perspective – two of the most significant contributions in launching the Italian Renaissance.

Of course, Donatello and so many others benefit from this 'rebirth', as we know from his collaboration with Brunelleschi at the Sagrestia Vecchia.

We finish the room with Donatello's Crocifissione (c1455) and his own terracotta La Madonna di Via Pietrapiana (1450-55). The Madonna is a highly publicized recent acquisition; unglazed but full of textures, it is a poignant and elegant ending.

We climb the eastern stairs to the Sala degli Avori , a vaulted space filled with, among other things, cases of ivory figurines. Large, striking frescoes are on either end of the hall, but we learn that these are 'falsario ottocentesco' – nineteenth century forgeries.

The adjoining hall, the Sala Carrand, is split by a line of fabric panels; on the other side, workers seem to be preparing the windows. Turning to the east, through a stone archway, we discover a room covered with painted walls. Il Bargello, so famous for its sculpture collection, includes a whole room filled with frescoes by Giotto.

Imagine this chapel as part of a prison, these images offering a beautiful but stark lesson in justice – this room was the last stop for the condemned on death row before their sentence was carried out.

The Cappella di Maria Maddalena ('Cappella del Podestà', bottega di Giotto, 1330-37) is a faded, fragmented version of the Cappella degli Scrovegni ('Cappella dell'Arena', Giotto, c1305). The history of the Palazzo has taken its toll on this room, but there is enough left of the fresco cycle to appreciate one of the brilliant master's last works (have a look around).

The altarpiece (Trittico, Giovanni di Francesco, 15th century) is in inside arch on the eastern wall (top image). The lower third of the walls is from a later re-painting, with a trompe-l'œil marble wainscot and cornice trim with dentils. In the center of the eastern wall is a lancet with stained glass (the other lancets in the north wall have 'venetian' circle-glass). At the top is the Pantocratore, and below Him is Paradiso, and all the saints with their halos, fading upward.

The figures in these lower registers, do not have halos, but we assume they are the 'saved', the 'eletti'. The museum marker in the room explains that among them is Dante Alighieri – condemned here in the Bargello by the Podestà and exiled from Firenze. A local legend says that Giotto himself painted Dante's portrait on the wall, holding a sprig from an apple tree and his book the Divina Commedia.

Patches of paint remain in the ogival vault. The side walls contain panels that tell the stories of Santa Maria Maddalena (south wall) and San Giovanni Battista (patron saint of Firenze, north wall). Between the two windows of the side wall is the figure of San Venanzio with an inscription that dates the completion of the frescoes to 1337, the year of Giotto's death.

An illustration of Dante's Inferno takes up the west wall. Lucifero, as Dante describes, has three faces, bat wings, and giant beasts at his feet.

The frescoes (14th century) in the adjoining Sagrestia are in much better shape and give a hint to the appearance of the Cappella as it was.

Back in the Sala Carrand, the display cases are tightly arranged in the area left by the temporary partitions. We inspect some of the medieval household furnishings and fittings: clocks, calendars (astronomical calculators), locks and keys.

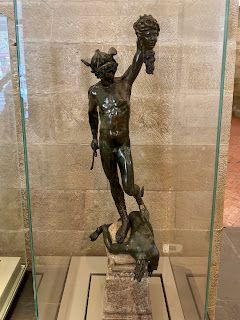

Doubling back to the far end of the Sala degli Avori, we enter the Verone (loggia); a flock of bird statues greets us. The three large marble pieces are: Mercurio and L'Architettura ('Allegory of Architecture', Giambologna, 16th century) and Giasone ('Jason', Pietro Francavilla, 1589).

The Verone brings us back to the Scala Goticheggianti ('Gothic stairway', 14th century) in the Cortile.

The so-called Crocifisso Gallino (c1495-97) is sandwiched in glass nearby. Once attributed to Michelangelo, it is very reminiscent of the Crocifisso (1492) in Santo Spirito.

Next to the Crocifisso Gallino is the Tondo Pitti (c1503-05), a large marble roundel with the Madonna col Bambino emerging from the unfinished background. The pose is like the Brugse Madonna (1501-1504) we saw earlier this year: Mary reads a book while trying to restrain the Baby Jesus, who is freestanding rather than seated. We can see the chisel marks around the child behind Mary, San Giovannino, and the around the edges of the irregular shape of the tondo.

In the center of the room is a model of the statue of Perseo (1545-54) by Benvenuto Cellini as well as its elaborate, original base; a copy of Perseo is in the Loggia dei Lanzi. The side story here is that Cellini, experimenting with large cast bronzes, wanted to put Medusa (her head is held by Perseo) in the middle of the Piazza della Signoria, all the figures turning to stone.

Other well-known pieces include Cellini's bust of Cosimo I (1545-47), and Michelangelo's unfinished Apollo/David ('Apollino', c1530).

With the Salone di Donatello closed, the one highlight we miss is his San Giorgio (1415-17). This sculpture cannot be moved as it is set within an architectural niche built into the wall. However, like the Perseo, this is the original, and a copy now sits in its intended public space, Orsanmichele (14th century).

Orsanmichele is just a short walk, so we head there to finish our tour. This is a building with an unusual history. Originally an open-arched market hall where grains are stored and exchanged, it is enclosed and then becomes a church. It is famous for the sculptures representing the patron saints of the trade guilds; San Giorgio represents the Arte dei Corazzai e Spadai (armourers and swordsmiths).

We approach Orsanmichele from the east, and the first pieces we see are Incredulità di San Tommaso (Verrocchio, 1467-83) and San Luca (Giambologna, 1597-1602). Turning to the north side, we find San Pietro (Brunelleschi, 1410-12), and Quattro Santi Coronati (Nanni di Banco, 1409-17). It's an amazing 'who's who' of Renaissance sculptors.

Finally, we reach Donatello's San Giorgio, who looks strangely under-sized for his niche. Pictures from the Bargello, show a textured surface behind the figure, but here there are only smooth, curved blocks. A weapon is clearly missing from his gripped right hand. In the relief panel below, he kills the dragon, but the figure represents the moment just before the fight. The determined expression on the his face looks every bit like Michelangelo's David (1501-04) on the verge of battle – a boy about to become a legend.

Continuing around to the south wall, we reach Donatello's San Marco (1411-13) and the Madonna della Rosa (c1399) attributed to Piero di Giovanni Tedesco, which has a decidedly 'Giotto-esque' late-Gothic look.

To complete our day, we decide to climb to San Miniato al Monte (11th century) to see the sunset: from the Ponte Vecchio, along the Arno, through the Porta San Miniato, into the Giardino della Rose, past the Piazzale Michelangelo, and on up to the old church.

No comments:

Post a Comment