Our time in London (pop 8.67 million in 2022) is planned around seeing friends and visiting museums. We start on the 'ground level, by browsing the stalls of the Bermondsey Antiques Market, a weekly event held in Bermondsey Square. We recall the day of one of our firsts visits to the Gulbenkian began with a visit to the Feira da Ladra, and how a dive into 'low culture' changes our perspective on 'high culture'.

We realize this extreme contrast at the Tate Modern, one of world's most significant contemporary art museums. The main gallery is in the old Bankside Power Station (Herzog & de Meuron, reuse 2000), but we approach from the south and enter from 'The Switch House' (Herzog & de Meuron, expansion 2016), a pyramidal form screened with offset stone Lego bricks.

The design of the De Young Museum in San Francisco (2005), which we enjoyed many times when we lived in The Bay Area, is by the same architect, but there the tower is an inverted pyramid, and the screen is perforated copper – interesting the contrast between designs for San Francisco and London.

We meet our friends inside. It's Oscar season, and our conversation wanders to the movie 'The Brutalist', and Brutalist architecture, as we are met by a number of spare, concrete forms: spiral stairs, piers, walls, and beams. But these forms disengage and float; there is a lightness and a sense of plasticity that defies the Brutalist association.

Other elements seem to be left from the building's industrial past and so do not hold an intentional expression. Still, it's fun to consider what blurs or separates industrial construction from architectural design.

As we consider this, we discover dynamic openings and gaps that permit views to the plaza outside and into the old Power Station.

We begin our museum tour on the third level, in a gallery entitled 'Performer and Participant' and the costumes and props from Monster Chetwynd's "A Tax Haven Run By Women" (2010-11). Again, the distance between these pieces and the clothes on the racks at the flea market seems remarkably short.

Suspended mirrors and a line of blue painter's tape fill the next room; this is an "Untitled" (2001) work by Edward Krasiński. We enliven the piece by moving around the room, changing our views, adding our reflections, stooping down and aligning the blue tape.

An adjoining gallery features work from the experimental Japanese Gutai Art Association, such as Yūko Nasaki's "18281 holes" (1962), in which the canvas (thick paper?) is meticulously pierced from both sides.

We take the elevator up to the Level 10 cafe and spend time reconnecting with our friends and enjoy tall, layered space as well as the framed vistas out across the Thames to St Paul's Cathedral (Christopher Wren, 1675-1710) and The Shard (Renzo Piano, 2013).

After coffee, we descend to the fourth level, where there is a bridge between the tower and the Power Station with lovely, long views into the 'Turbine Hall' (top image).

The fourth-floor acts as a start point and gathering space. We step down to a long balcony overlooking the 'Turbine Hall' with upholstered chairs. The entrance to the main gallery shows a series of square panels, from the "Thamesmead Codex" (2021) by Bob and Roberta Smith – transcribed pieces of political street art.

Common objects are given new story-telling potential in the next gallery, themed 'Materials and Objects'. Images of simple, natural objects are de-contextualized on colored panels in Robert Zhao Renhui's "A Guide to the Flora and Fauna of the World" (2013). Household items with some religious content are gathered in a chapel-like frameworks in Meschac Gaba's "Art and Religion Room" (1997-2002).

In another room, Barbara Chase-Ribaud's "Zanzibar (Brown Element)" (1974-75) is juxtaposed with large prints from Robert Motherwell's "Africa Suite" (series, 1970); the black forms are in conversation.

The next room holds "discrepancies with T.P. (II) – random intersections #29 – Lena #8.1" (2012–23) by Leonor Antunes (we saw her show at the CAM/Gulbenkian, see earlier post). Here, loose textiles, rope, wire and leather hang from frames, creating a play of materials, line, light, and shadow.

Two enigmatic pieces expand the theme. Robert Gober's "Untitled" (1989-92), a leg at the end of a dim corridor, is quiet and surreal. While Nalini Malani's "In Search of Vanished Blood" (2012-20) is all spectacle and noise – wall-covering images projected through painted, rotating cylinders accompanied by a loud soundtrack.

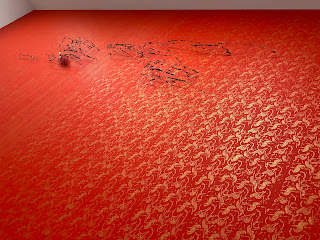

Two iconic pieces complete the set. First is one of Kurt Schwitters' 'Merz' found-object collages, "Picture of Spatial Growths – Picture with Two Small Dogs" (1920-39). And finally, we finish with David Hammons' "Untitled" (1995), a brightly painted, patterned wall interrupted by hoops of wire with balls of human hair (we assume it's his own).

Energized, we head to the Restaurant on the sixth floor for a good meal and more conversations.

After lunch, we drop down to the second level and finish where we might have begun, with 'Start Display', galleries design as an introduction to the Tate's collection – a kind of 'greatest hits'. Though we may have toured the museum backwards, we get to finish with fireworks.

Henri Matisse's glorious "The Snail" (1953) by is much larger than we anticipated, a swirl of colored pages three meters tall and wide. These colors echo in Ellsworth Kelly's color lithographs (c1960's), but with a precise and calm balance.

"The Invisibles" (1951) by Yves Tanguy invents disquieting forms in a stormy, atmospheric landscape. And "Dish of Pears" (1936) by Pablo Picasso is inventive in a different way, takes a similar palette and makes it inviting and playful – especially the decorative curls in the corners.

We imagine two pairs of masters are given the same paints and asked to create 'something new'.

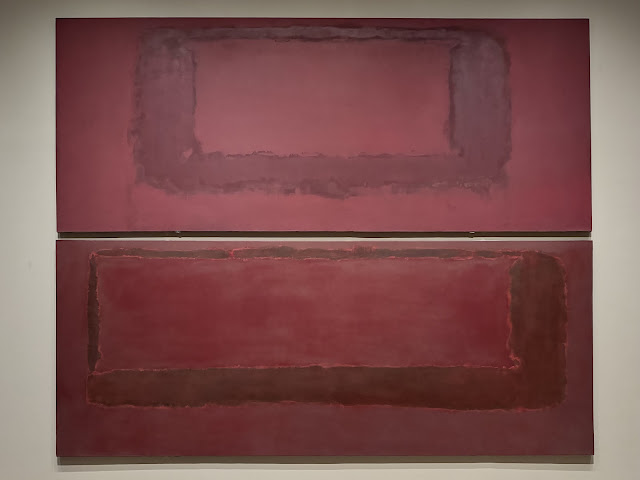

We complete the 'hits' and a large gallery dedicated to Mark Rothko's "Seagram Murals" (1958). It is a foreboding conclusion: immense canvasses drenched in deep, earthy hues. A sheen on the surface makes them impenetrable; architectural forms seem to emerge from a hazy twilight:

I was much influenced subconsciously by Michelangelo’s walls in the staircase room of the Medicean Library in Florence. He achieved just the kind of feeling I’m after – he makes the viewers feel that they are trapped in a room where all the doors and windows are bricked up, so that all they can do is butt their heads forever against the wall. (James E. B. Breslin, Mark Rothko: A Biography, Chicago, 2012, p 400)

We exit through the 'Turbine Hall' and get an look from beneath Mire Lee's "Open Wound" (also, top image; 2024), diaphanous rags suspended under the luminous geometry of the industrial skylights. Outside, we get a better sense of the way 'The Switch House' mediates between the old Power Station and the city's glass and steel skyscrapers.

Returning to the Bermondsey District to meet friends for dinner, we can see The Shard and the full skyline of London – the red lights of the construction cranes sprinkled throughout, paused while building new towers.