We stop for hornazo – so delicious, but not health food. A little goes a really long way. After our snack, and with the skies clearing, we are ready to head out, having spent the morning indoors. We decide to take the view of the river, and head south.

The Casa de los Abarca Alcaraz (16th century) is similar, though less ostentatious. All the signage is done is the now familiar 'vítor' graffiti style, with the letters fading and re-applied. The plateresque string courses and trim act as boundaries or dividers.

The Jardín de la Merced offers an expansive view of the river walk and the Puente Romano (1st Century BC?). We can make out el verraco del puente staring down the approach to the bridge. This is near the southwestern corner of the kink, the 'Tormes gumdrop'. The river seems shrunken under the arches of such a lengthy viaduct.

Leaving the Jardín and moving east, we investigate the facade of the Monumenta Salamanticae (Iglesia de San Millán, 18th century), a modest beauty.

The Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica (Joaquín de Churriguera, 1720) wins for having the best name, and looks more Baroque than plateresque (neoplateresco); it holds an archive of material documenting the time of the Spanish Civil War – this was, at the time, a barracks for Franco's Guardia de Regulares.

Near the cathedral complex, we enjoy more views from the Huerto de Calixto y Melibea. Salamanca's historic center is generally free from traffic, but here we see and sense the energy from the circular artery that surrounds our garden.

The last major site to visit is the Convento de San Esteban (16th century). From the Plaza del Concillo de Trento, we cross a small pedestrian bridge over the Arroyo de Santo Domingo and onto the checkerboard Plaza de San Esteban.

The late afternoon sun is just leaving its last rays on the Calvario near the top of the fachada. With the same alchemy we saw last night, the stunning Crucifixión glows gold. San Pedro (with keys) is on His right, and San Pablo (with sword) is on His left, about to fade into the shadows; the Pantocrátor at the top is already there. The quality of the sculptural renderings is fantastic (Juan Antonio Ceroni, 17th century), as is the architecture with narrow, decorative posts in front of wide, almost classical pilasters. The presentation may be 'plateresco', but the execution should just be called Renacimiento Español.

In the smaller arch below is the Martirio de San Esteban (Ceroni, 1610); he was stoned to death. With the light cast from the bell tower, a small spot dramatically strikes the bald head of the attacker behind him. The inscription states his final words:

Domine ne statuas illis hoc pecatu[Lord, do not lay this sin to their charge]

The main door is finished in raised diamonds. As this is a Dominican convent, to the left of the door is Santo Domingo, with a star on his forehead and a dog at his feet. The female saint to the far right may be Santa Teresa, the martyred Carmelite nun from the neighboring city of Ávila.

The visitors' entrance is from the Doric loggia to the south of the Plaza, under the bell tower, and we begin in the Claustro de los Reyes. We are met by an interesting 'corner niche' Anunciación; poor Gabriel has lost his head.

Dominican friars literally oversee the door; San Pedro de Verona martyred with a sword in his head, is carved over one. Heads are getting some rough treatment. San Domingo, marked again by the star and the dog, is over the door in the northeast corner which leads to both the Iglesia and the Sacristía.

The door leads to an amazing white stone staircase, known as the Escalera de Soto (16th century), with a coffered arch and a lacy vault. The Sacristía (17th century) is beyond the door in the corner, tight under the arch. When we go under, it opens to a cavernous triple-height room, all classical order and proper Corinthian pilasters.

Looking back, we notice the door to the staircase is offset by a shallow, diagonal barrel vault, so as not to disturb the symmetry. Knowing that the low arch is on the other side, the architect would not have been able to keep it centered otherwise.

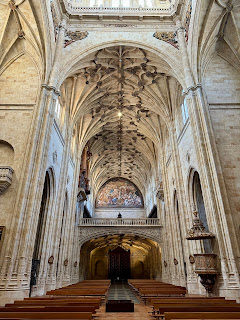

Another door from the stair hall connects to a dark, narrow hall with a vaulted ceiling with a lantern. The hall is in place of a side chapel, and so we immediately enter at the chancel.

The ogrnate Baroque altarpiece (1693) is by José Churriguera and integrates a painted scene of the Martirio de San Esteban (Claudio Coello, 1692).

The center is covered by a cross vault with side lights. Aligning the floor plan, we understand that the grand stair is in the place of the south transept. The Capilla del Rosario in north transept includes an unusual back-lit altar and a scene painted directly on the stone blocks of the Coronación de la Santísima Virgen (Antonio Villamor, 18th century).

Unlike the cathedrals, the Coro of this church is in a loft near the front. It contains an eye-catching painting by Antonio Palomino of Triunfo de la Iglesia (1705).

The Organ is mounted just back of the Coro. The north chapel near the front includes a stained-glass piece with a man feeding dogs, cats, and rats. The two piers near the crossing have niches holding Gabriel and Mary, creating an Anunciación across the nave.

Completing our exploration, we ascent the Escalera de Soto to the upper cloisters.

By now, we 'get it': old Spanish buildings in this region are monochromatic. So, the surfaces and shadows do all the heavy lifting – no paint, no tiles, not even a mix of materials. On a late, sunny afternoon, they simply absorb the colors of the landscape and of the atmosphere. And it's enough. It's more than enough, it can be sublime.

In a miraculously maintained medieval cloister, we can be monks. It is silent, yet the whole world is present.

From the Claustro Alto, we access the Coro. Remnants of stained-glass panels break the monochrome, but their stories are illegible. Our gaze follows the curvilinear tracery of the vaults to the altar, and with our eye-line right near the center, the gilt elements sparkle and infuse the edges.

We turn, and though we cannot enter the area with the choir stalls, are overwhelmed by the vivid animation of Palomino's of Triunfo. The carriage wheel anchors the composition; the artist has signed the rim. Out front, a team of horses tramples the evil that threatens the church, as San Domingo (mark on his forehead, just above the wheel, just below God) provides direction. At the back of the carriage is the Pope, with his Bible open to Matthew 1:1 – back to basics, start anew:

Libre generationis Jesu Christi[The book of the generation of Jesus Christ …]

So that's today's lesson. The story never ends, we must make new, renew, anew. Architecture is a communal art, and everyone adds a layer – add your own creatures, your own space people.

Having covered the southern, 'fat' end of the 'gumdrop', for our after-dinner walk, we venture north. Near the Puerta de Zamora the old city ends, and traffic flashes by. Tucked into this urban pocket is the Iglesia de San Marcos (12th century). We enter just as services start, so cannot offer any pictures. Big crowd tonight, but we had not intended to stay. At the first opportunity, we slip out. But after nearly a thousand years, life in this church goes on.

No comments:

Post a Comment